The Comparison of My

Information Formula and Floridi’s Information Formula

Abstract: Floridi considered the matters of truth-False and

always-true-propositions in setting up his semantic information formula, but

the matter how the size of logical probability of a proposition affects

information amount as Popper pointed out. Floridi’s information formula is also

not compatible with

Key word: semantic information, formula, Popper, Shannon

我的语义信息公式和Floridi的语义信息公式比较

鲁晨光

摘要:Floridi的建立语义信息公式时考虑了对错问题和永真命题问题, 但是没有考虑Popper指出的命题逻辑概率大小对信息量的贡献, 也不和Shannon信息公式兼容。 本文将我的信息公式和Floridi的信息公式做了比较, 试图说明我的信息公式更加合理。

关键词:语义信息,公式,Popper, Shannon

1. 引言

度量语义信息必须考虑事实检验。 就检验来说, Floridi的思路(参看附录, 摘自[1])和我的思路是一样的。我认为, 语义信息量公式要能保证:

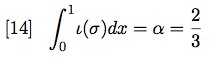

1)对错问题;说对了信息就多,

说错了信息就少。比如你说“明天下雨“, 实际上第二天没有雨, 信息就少(我说是负的)。如果第二天有雨, 信息就是正的;

2)永真命题不含有信息, 永真命题比如:“明天有雨也可能无雨”,“一加一等于二”。

3)把偶然事件或特殊事件预测准了,信息量更大。比如你说“明天有特大暴雨”(偶然事件),“明天股市上涨1.9%, 误差不超过0.1%”(特殊事件)。如果说对了,信息量就更大。用Popper的话来说就是:预测经得起更严峻的检验[2], 则信息内容更丰富。

4)和Shannon信息公式[3]兼容。

Floridi 建立信息公式的时候,充份考虑了前两个问题。没有考虑后两个问题。

下面我们通过分析比较,看Floridi的信息公式存在的问题。

2.

Floridi的语义信息量公式

他举例说:事实=晚上有三个客人来用晚餐;三个预测:

(T)今晚可能有, 也可能没有客人来用晚餐;

(V)会有一些人来用晚餐;

(P)有三个客人来用晚餐。

其中, 第一个(T)是永真命题, 不含有信息; 第二个(V)有些信息; 第三个(P)信息量最大。

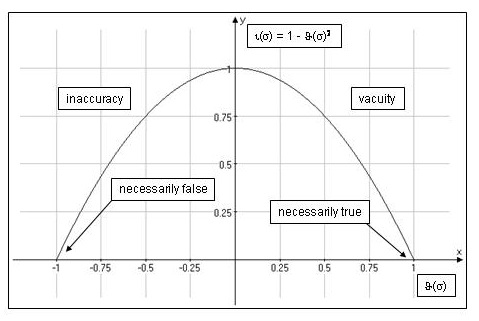

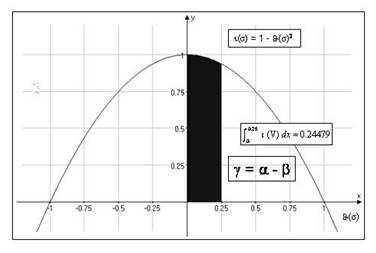

Floridi用w表示事实,

σ表示预测值,θ表示事实w对σ的支持度。用

ι(σ) = 1 − θ(σ)2

(1)

表示信息度(degree of informativeness,参看附录Figure 5)。

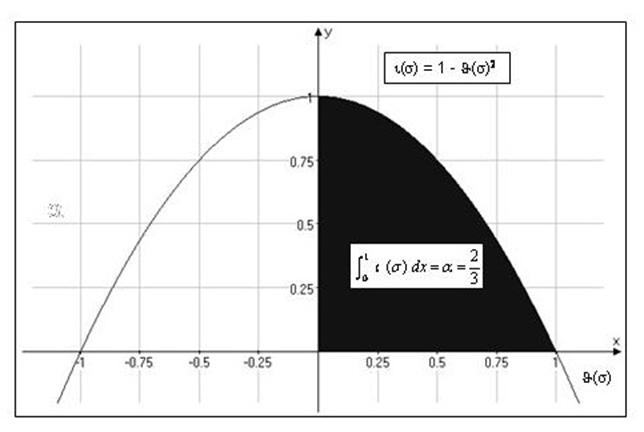

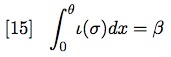

信息度还不是信息量,它对支持度θ积分才是信息量。预测σ提供的信息是多少呢?Floridi说它等于

γ(σ) = log(α − β)

(2)

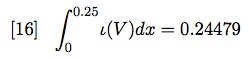

其中α是最大可能信息,等于2/3, 即抛物线右边部分(Figure 6中阴影部分)面积。其中β是V提供的信息,等于0.24479(很像我后面说的先验逻辑概率)

上面信息量公式(2)有什么问题呢?

1)它能保证序言中说的1)和2), 但是不能反映Popper的严厉检验,

那就是给予更偶然, 更特殊的命题以更高的评价。 比如,考虑预测:P1=“晚上有客人――两老头和一女孩――来用晚餐”,

如果说对了,信息量应该更大。Floridi的公式不能得到这个结论,因为ι(σ)上限有限, 等于1.

2)为什么事实w对P的支持度θ是0? 为什么不是1? 显然,如果w对P的支持度θ=1, 就得不到结论――P的信息量最大。 Floridi可能想说明P的先验逻辑概率是0或很小。但是它的公式不能反映先验和后验问题。

3)假如事实是10个客人,P(说有3个客人,

说错了)的信息量是多少?这时候公式如何处理令人费解。

4)和Shannon信息量公式相差太远,难于理解。

我以为问题的根源是Floridi没有考虑命题的先验真假和后后验真假的区别。命题T之所以不提供信息, 是因为无论是先验还是后验,它都是真的; 而P只有后验是真的, 先验为真的可能性很小。

3. 我的语义信息量公式

我用股市指数预测来说明我的信息量公式, 因为指数预测比客人数量预测更具有一般性。

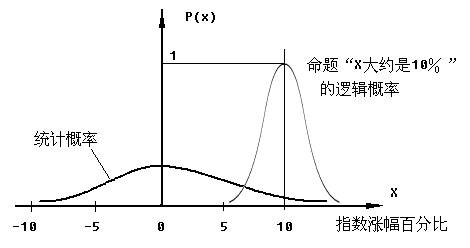

经典信息论用到的概率可谓统计概率,而反映命题真假的概率是逻辑概率。两者区别参看图1。

图1 统计概率和逻辑概率比较

我们可以统计某个股市多年来日升跌幅的频率, 当天数大到一定程度后,相对频率(在0和1之间)就趋向某个确定值,这个值就是概率或统计概率。命题的逻辑概率是事实xi一定时,命题yj或yj(xi)被不同的人判断为真的概率。比如命题yj=“指数升幅接近10%”在指数实际升幅X=10%时被判定为真的逻辑概率是1;随着误差增大,逻辑概率渐渐变小;误差超过5%时逻辑概率接近0。

从数学的角度看,两种概率的区别是:对于P(xi), 一定有概率之和等于1, 即

![]()

(3)

而逻辑概率Q(yj为真|xi)的最大值是1,求和之后一般大于1。

假设使yj为真的所有X构成模糊集合Aj,逻辑概率Q(yj为真|xi)就是xi在Aj上的隶属度,那么我们也可以用Q(Aj|xi)表示xi在Aj上的隶属度和命题yj(xi)的逻辑概率。

命题yj对于不同X的平均逻辑概率(也就是谓词yj(X)的逻辑概率)是:

![]()

(4)

我们定义语义信息公式

![]()

(5)

其含义是:

(6)

由图2可见,事实和预测完全一致时,即xi=xj,,信息量达最大;随着误差增大, 信息量渐渐变小; 误差大到一定程度信息就是负的。这是符合常理的。

图2 语义信息公式图解

用这个公式可以保证:

1)永真命题(比如“股市每天可能涨也可能不涨”)信息量是0, 因为先验和后验逻辑概率都是1.

2)错的命题信息量是负的;

3)越是能把偶然的涨幅(比如涨幅10%比涨幅1%更偶然)预测准了, 或者越是预测得精确(比如预测“股市明天涨幅大约是5%”比“股市明天会涨”)并且正确,信息量越大。

因为对偶然事件的预测和更精确的预测,逻辑概率更小(由图1 和公式4可见)。

这一公式同样可以度量测量信息(比如温度表信息),一般预言信息, 感觉信息[3]。

自然也可以度量客人数量预测信息。

4. 用我的信息公式度量客人数量预测信息

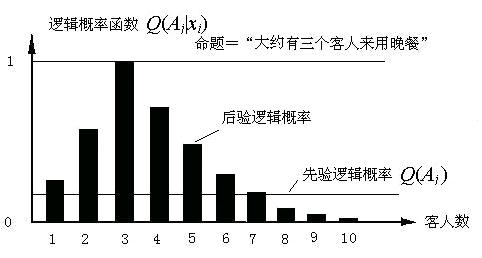

我们用这个公式来度量Floridi例子中T, V, P三个预测的信息看看。这时候xi就是w, 三个预测的后验逻辑概率都是1, 但是先验逻辑概率不同。

首先看T。 因为先验后验逻辑也是1,

所以信息(量)等于0.

再看V。先验逻辑概率小点,假设是1/4(即3/4的情况下没有客人来), 则信息等于log(1/4)=2比特。

再看P。先验逻辑概率更小,假设是1/16,

则信息等于log(1/16)=4比特。

假设P变成P1=“晚上有三个客人――两个老头和一个女孩――来用晚餐”,则先验逻辑概率更小,信息量更大。

如果我们用精确的方式理解语言P, 则不是三个人来都算错,信息量是负无穷大。但是日常生活中,我们总是用模糊的方式理解语言,2个或4个人来也算大致正确, 所以P的逻辑概率函数应该大致如下:

图3 模糊命题(或清晰命题模糊理解时)的逻辑概率函数

这时候,预测不同人数语句提供的信息是正还是负, 取决于后验逻辑概率是否大于先验逻辑概率。大于则信息是正的, 等于信息是0, 小于消息是负的。这符合常理。

模糊逻辑概率也可以来自统计, 参看我的网上文章《借助罩鱼模型从Hartley信息公式推导出广义信息公式》[1]。从这篇文章也可以看出:我的上述语义信息公式也可以通过经典信息量公式I=log[P(xi|yj)/P(xi)]推导出来。

关于我的语义信息研究,更多讨论见文献[4.5,6]。

参考文献

[1] Floridi, L., Semantic Conceptions of Information, in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, see http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/information-semantic/

[2] 波普尔,猜想和反驳——科学知识的增长[M],上海:上海译文出版社,1986.

[3] Shannon, C. E. A mathematical theory of communication[J],Bell System Technical

Journal, 1948, (27),379-429,623-656

[4] 鲁晨光,广义信息论[M],中国科学技术大学出版社,1993.

[5]Chenguang, Lu (鲁晨光), A generalization of Shannon's information theory[J]

, Int. J. of General Systems, 1999, 28(6),453-490

[6] 鲁晨光, 广义熵和广义互信息的编码意义[J],

通信学报,

1994, 5(6), 37-44.

附录:Floridi信息公式说明

(参看网页:http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/information-semantic/ )

Suppose there will be exactly three guests for dinner

tonight. This is our situation w. Imagine we are told that

|

(T) |

there may or may not be some guests for dinner tonight;

or |

|

(V) |

there will be some guests tonight; or |

|

(P) |

there will be three guests tonight. |

The degree of informativeness of (T) is zero

because, as a tautology, (T) applies both to w and to ¬w. (V)

performs better, and (P) has the maximum degree of informativeness because, as a

fully accurate, precise and contingent truth, it “zeros in” on its target w.

Generalising, the more distant some semantic-factual information σ is from its target w, the larger is the number of situations to

which it applies, the lower its degree of informativeness becomes. A tautology

is a true σ that is most “distant” from the world.

Let us now use ‘θ’ to refer to the distance between a true σ and w. Using the more precise vocabulary of situation logic, θ indicates the degree of support offered by w to σ. We can now map on the x-axis of a Cartesian diagram the values

of θ given a specific σ and a

corresponding target w. In our example, we know that θ(T) = 1 and θ(P) = 0. For the sake of simplicity, let us

assume that θ(V) = 0.25 (see Floridi [2004b] on how to

calculates θ values). We now need a formula to calculate

the degree of informativeness ι of σ in relation to θ(s). It can be shown that

the most elegant solution is provided by the complement of the square value of θ(σ), that is y = 1 − x2. Using the

symbols just introduced, we have:

[13] ι(σ) = 1 − θ(σ)2

Figure 5 shows the graph generated by equation [13]

when we include also negative values of distance for false σ; θ ranges from −1 (= contradiction) to 1 (=

tautology):

Figure 5: Degree of informativeness

If σ has a very high degree of informativeness ι (very

low θ) we want to be able to say that it contains a large

quantity of semantic information and, vice versa, the lower the degree of

informativeness of σ is, the smaller the quantity of

semantic information conveyed by σ should be. To calculate

the quantity of semantic information contained in σ

relative to ι(σ) we need to calculate

the area delimited by equation [13], that is, the definite integral of the

function ι(σ) on the interval [0, 1].

As we know, the maximum quantity of semantic information (call it α) is carried by (P), whose θ = 0. This is

equivalent to the whole area delimited by the curve. Generalising to σ we have:

Figure 6 shows the graph generated by equation [14].

The shaded area is the maximum amount of semantic information α carried by σ:

Figure 6: Maximum amount of semantic information α carried by σ

Consider now (V), “there will be some guests tonight”. (V)

can be analysed as a (reasonably finite) string of disjunctions, that is (V) =

[“there will be one guest tonight” or

“there will be two guests tonight” or

… “there will be n guests tonight”], where n is the reasonable limit we wish to consider (things

are more complex than this, but here we only need to grasp the general

principle). Only one of the descriptions in (V) will be fully accurate. This

means that (V) also contains some (perhaps much) information that is simply

irrelevant or redundant. We shall refer to this “informational

waste” in (V) as vacuous information in (V). The amount of

vacuous information (call it β) in (V) is also a function

of the distance θ of (V) from w, or more generally:

Since θ(V) = 0.25, we have

Figure 7 shows the graph generated by equation [16]:

Figure 7: Amount of semantic information γ carried by σ

The shaded area is the amount of vacuous information β in (V). Clearly, the amount of

semantic information in (V) is simply the difference between α (the maximum amount of information that can be carried in principle by

σ) and β (the amount of vacuous

information actually carried by σ), that is, the clear area

in the graph of Figure 7. More generally, and expressed in bits, the amount of

semantic information γ in σ is:

[17] γ(σ) = log(α

− β)

Note the similarity between [14] and [15]. When θ(σ) = 1, that is,

when the distance between σ and w is maximum, then α = β and γ(σ) = 0. This is what happens when we consider (T). (T) is so distant

from w as to contain only vacuous information. In other words, (T)

contains as much vacuous information as (P) contains relevant information.